Although most people are familiar with Cubism and can recognize a Cubist painting, they tend to underestimate the significant impact it had on the Western art tradition that had been established in Europe over the course of five centuries beginning in the 15th century. In the early 1900s, the emergence of Cubism marked a profound departure from the artistic principles that had dominated since the Renaissance's resurgence of Greco-Roman art. While these conventions had already been challenged throughout the 19th century, Cubism dealt the final blow, opening the door for the avant-garde movements that would come next.

Cubism had a significant impact but at the same time, it was a relatively short-lived art movement, peaking over a decade before its lessons were absorbed or replaced. While sculpture played a role, Cubism was primarily focused on painting and dismantling the paradigm built on the rediscovery of classical aesthetics lost after Rome's fall.

This painting style, which spanned the Old Master period, sought to recreate nature by utilizing geometrical perspective or atmospheric effects (to evoke distance disappearing in a haze) and chiaroscuro (using gradations of light to create the illusion of form and space in three dimensions). The widespread use of oil paint glazes, and varnishes allowed light to penetrate through layers of color while minimizing visible brushwork, creating a tightly rendered surface that heightened the impression of reality.

Together, these elements created a metaphorical window through which a scene could be immortalized, making painting the primary tool for visually capturing existence until the invention of photography.

The ability to comprehend what was being depicted visually was a fundamental aspect of the artistic style that emerged during the Renaissance. Despite subsequent art movements such as Mannerism, Baroque, and Rococo, which pushed the limits of this concept, none completely discarded this core idea. Even 19th-century Impressionism adhered to this principle: for instance, a Monet haystack still retained its resemblance to an actual haystack.

Cubism not only marked the beginning of 20th-century art but also represented the resolution of issues that had preoccupied painters during the 19th century, particularly in its later decades. Over the course of about 75 years, French painting gradually moved away from the strict rules codified by the Academie des Beaux-Arts, which were based on the Old Master model. As time passed, these regulations were abandoned one by one, gradually weakening Academie's institutional power.

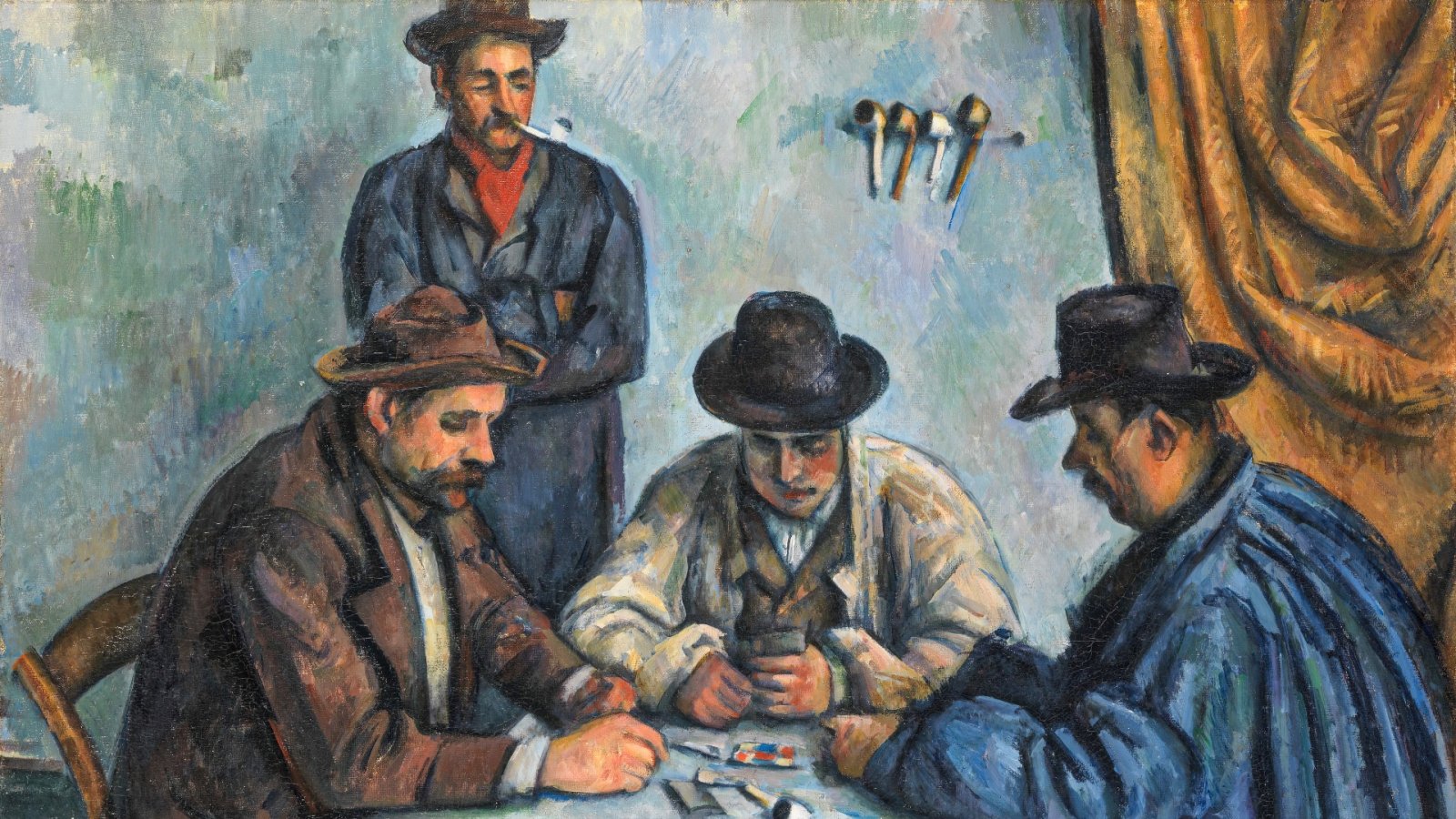

The most significant change was the abandonment of history painting, which had been the Academie's primary focus, in favor of previously less esteemed genres like portraiture, landscape, and still life, the latter of which was especially prominent in Cubism. Painting modern life, as poet and critic Charles Baudelaire had put it, replaced the exaltations of church, state, and classical mythology that had been central to Academic painting. The shift towards Cubism can be traced back to around 1880 when the Post-Impressionists emerged as a group. This collective included renowned figures such as Seurat, Gaugin, Van Gogh, and Cézanne, among others. Despite their diverse styles and subject matter, they all sought to push the limits of facture, which refers to the handling of paint.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

Pablo Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, completed in the summer of 1907, is considered the quintessential painting of both Cubism and modern art. Despite Picasso's reputation for misogyny and sexual exploitation, Les Demoiselles has stood the test of time as a pivotal work in art history.

Interestingly, the genesis of Picasso's masterpiece can be traced to two sources: his studio and the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. While working on the painting, Picasso visited the museum and was struck by a collection of tribal masks that had been taken from France's African colonies. This encounter had a significant impact on the composition of Les Demoiselles, which ended up being quite different from the artist's initial plans.

Set in a bordello on a street in Barcelona's red-light district, where Picasso had once had a studio, Les Demoiselles portrays five female nudes who are actually prostitutes displaying their bodies for male customers. In his original studies, Picasso had included two male figures, both sailors, with one being described as a medical student in his notes. However, after his visit to the Trocadéro, he removed these characters and altered the faces of three of the women to resemble the African masks he had seen.