Who was Judith Leyster and why was she significant?

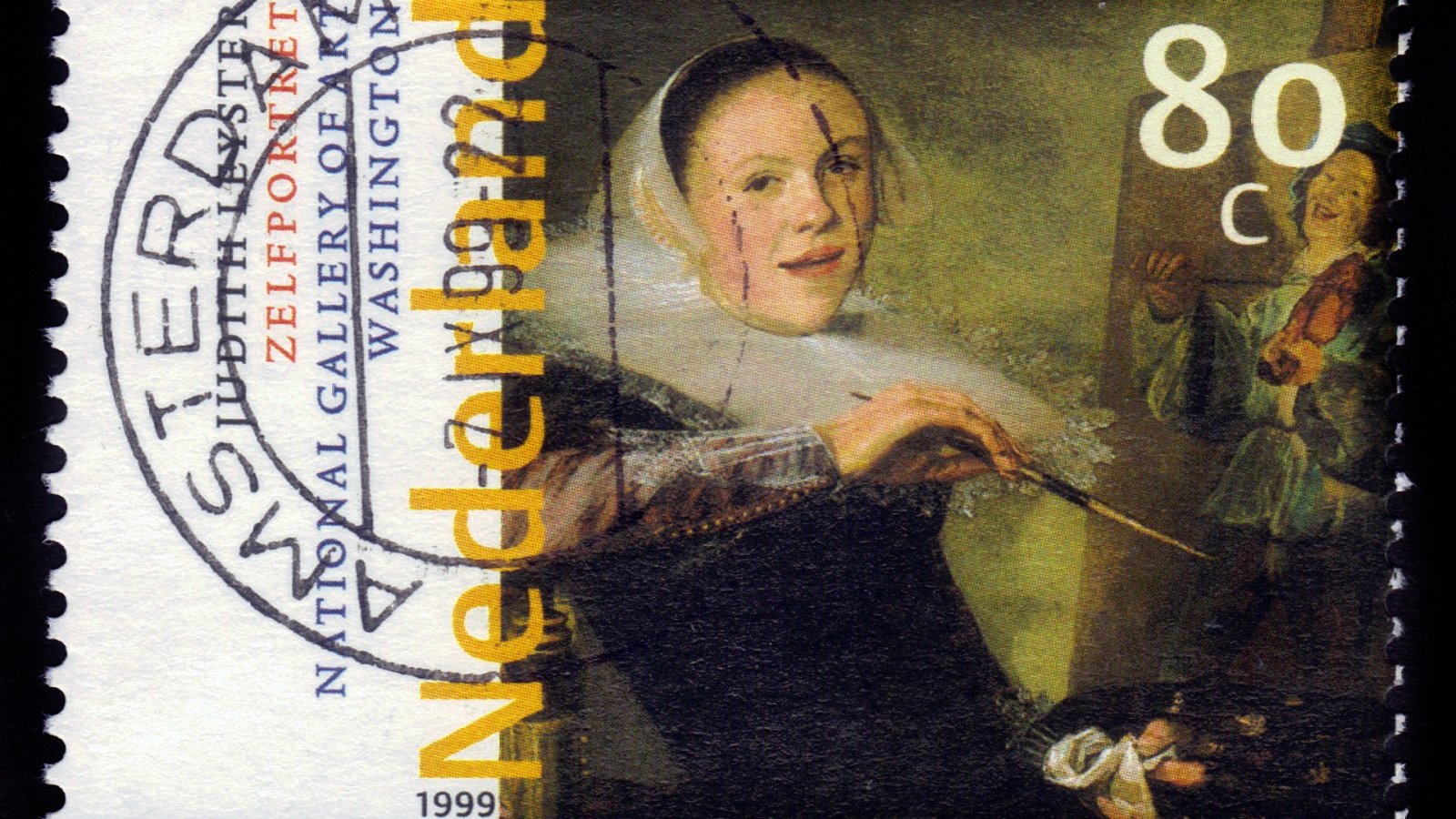

For over 100 years, Judith Leyster’s painting now at the Louvre was believed to be created by Frans Hals. This artwork showed a violinist reveling with a smiling woman, a common theme for the Dutch Golden Age artist. However, it was also made in the style of Judith Leyster, who was a peer of Hals and used a distinctive monogram with a shooting star. Her work was often mistaken for Hals, leading to a court case where British art dealer Thomas Lawrie sued the seller after spotting the monogram under a fake Hals signature. The court ruled it was not by Hals and Leyster received attribution. But today, only 35 works are attributed to her, making it significant when one broke the silence, such as the recently acquired "Boy Holding Grapes and a Hat” by the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire.

It’s now known that Leyster marked her works with a JL monogram with a shooting star, but her work was often mistaken for Hals due to ignorance of this monogram. This led to a court case in 1892 when Thomas Lawrie, an art dealer, found Leyster's monogram under a fake signature. As a result, the court ruled that the painting was not done by Hals, the art dealer got a partial refund, and a scholar wrote an essay attributing six more paintings to Leyster. So, when the painting entered the Louvre, it was listed by Leyster.

Who was she?

A rare female artist during Dutch Golden Age, she painted genre scenes, still lifes, portraits, and botanical drawings, known for capturing sitters from a "worm's-eye view" and incorporating dramatic lighting in her night scenes. With figures often arranged diagonally, she added liveliness to her works. Although much about her life is still unknown, scholars continue to study her impact on the Haarlem and Amsterdam art scenes.

Judith Leyster was born in Haarlem in 1609 and was the 8th child of Jan Willemsz and Trijn Jaspers. Her family named themselves after their brewery, adopting the surname Leyster. After Jan declared bankruptcy in 1625, Judith and her siblings had to work to support the family. However, it's unclear where she received her artistic training, but it's believed she either studied under Frans Pietersz de Grebber or Hals. Maria de Grebber, another female artist of the same age, was studying with her father, which may have also influenced Leyster. However, Leyster's early copy of Hals' painting "The Jester" suggests she was in Hals' workshop. Leyster was a prominent artist in the Dutch Golden Age. She joined the Haarlem painters' Guild of Saint Luke as one of the first women and became a master painter. She ran her own workshop and taught students. One student, Willem Woutersz, left Leyster's atelier for Hals' workshop, violating guild procedure. Leyster took the matter to the guild and demanded a quarter of the student's annual tuition but was only granted an eighth. Woutersz was not allowed to study with Hals. Leyster added her monogram to her works in 1629, soon after starting her career. One of her earliest surviving signed paintings is "The Jolly Toper", featuring a cheerful man holding an empty jug, his red cheeks matching the downward slanting feather in his cap.

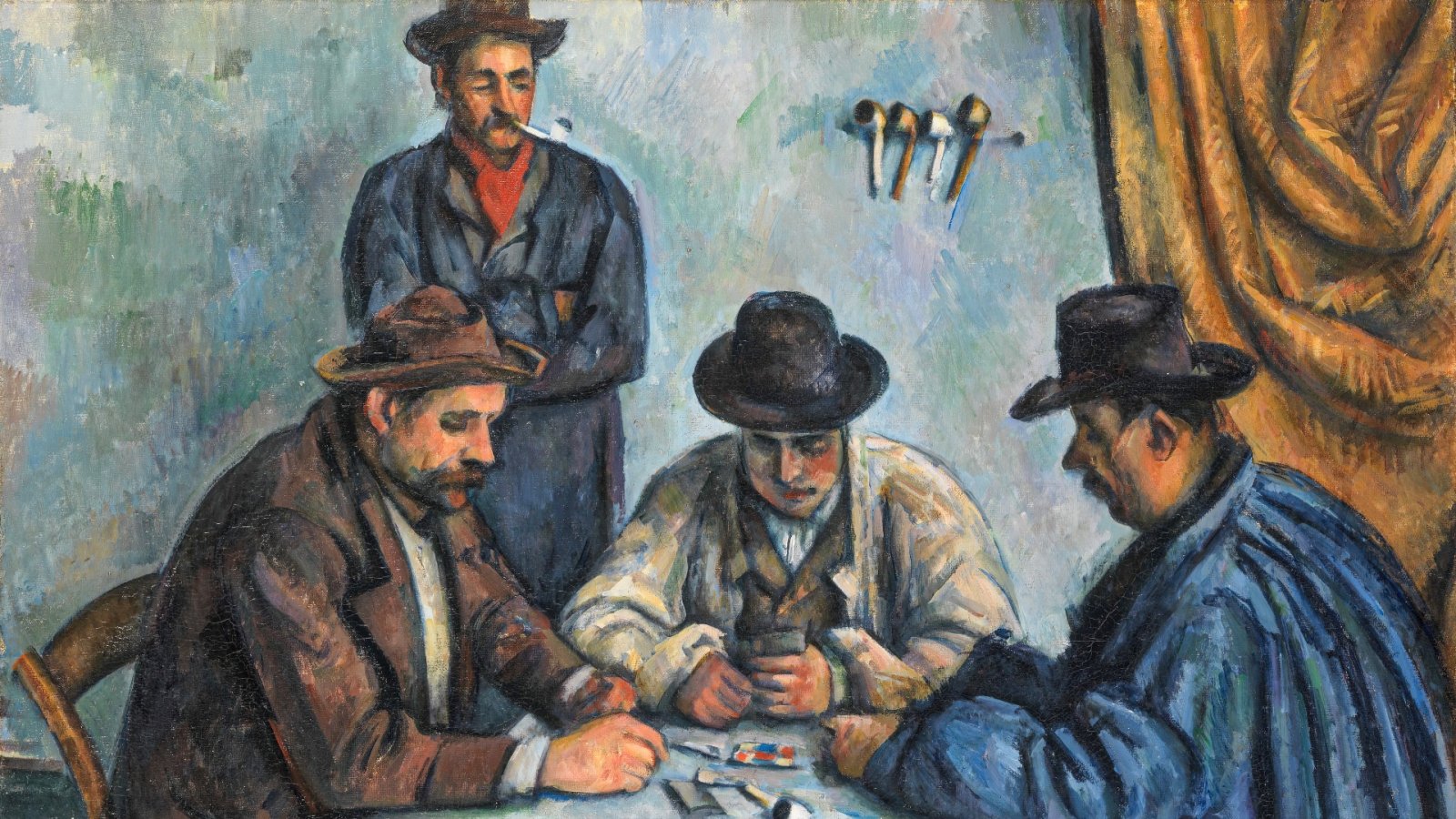

A curious thing about her is that her paintings often conveyed deeper messages about morality, often showing the dangers of vice through scenes of smoking, drinking, gaming, or music-making. For example, in The Last Drop, two young men that are ending a night of drunkenness are joined by an ominous skeleton, emphasizing the consequences of self-destructive behavior. What is more, Leyster's numerous pentimenti indicate she refined her compositions while painting rather than sketching beforehand. X-ray and infrared analysis have uncovered rejected compositions she painted over. Infrared reflectography of her Self-Portrait revealed that the original image was a girl with parted red lips, not the fiddler on an easel seen facing the artist.

Leyster married fellow Haarlem painter Molenaer, who produced various types of paintings, at age 26. Hals painted their portraits. The couple lived in Haarlem and Amsterdam. Most of Leyster's works predate her marriage, but some exceptions exist, such as a 1643 tulip catalog illustration, possibly created while she and Molenaer collaborated. A joint will in 1659 suggests they were both ill, and Leyster died three months later at age 50. Her gravesite is unknown as it was built over on a Heemstede farm.

Although Leyster's name faded into obscurity after her death, her paintings remained recognizable. They were often credited to other artists, most commonly Hals. For example, the painting "Boy Playing the Flute", featuring a young musician with a sunlit face gazing up towards an unseen window, was in the possession of the Swedish royal family for 150 years. Despite being monogrammed by Leyster, it was believed to be by Hals and a few more artists, before being correctly credited to Leyster.